Among the resistance groups that emerged in the wake of the coup are specialized drone forces like the Federal Wings and Cloud Wings, two units associated with the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army in Kayin state. Others, such as Shar Htoo Waw, serve as knowledge hubs for drone forces, providing training and materials for drone innovation and adaptation. Resistance groups, whether EAOs or post-coup armed groups, vary in their resources. This affects their capacity to access and use drones.

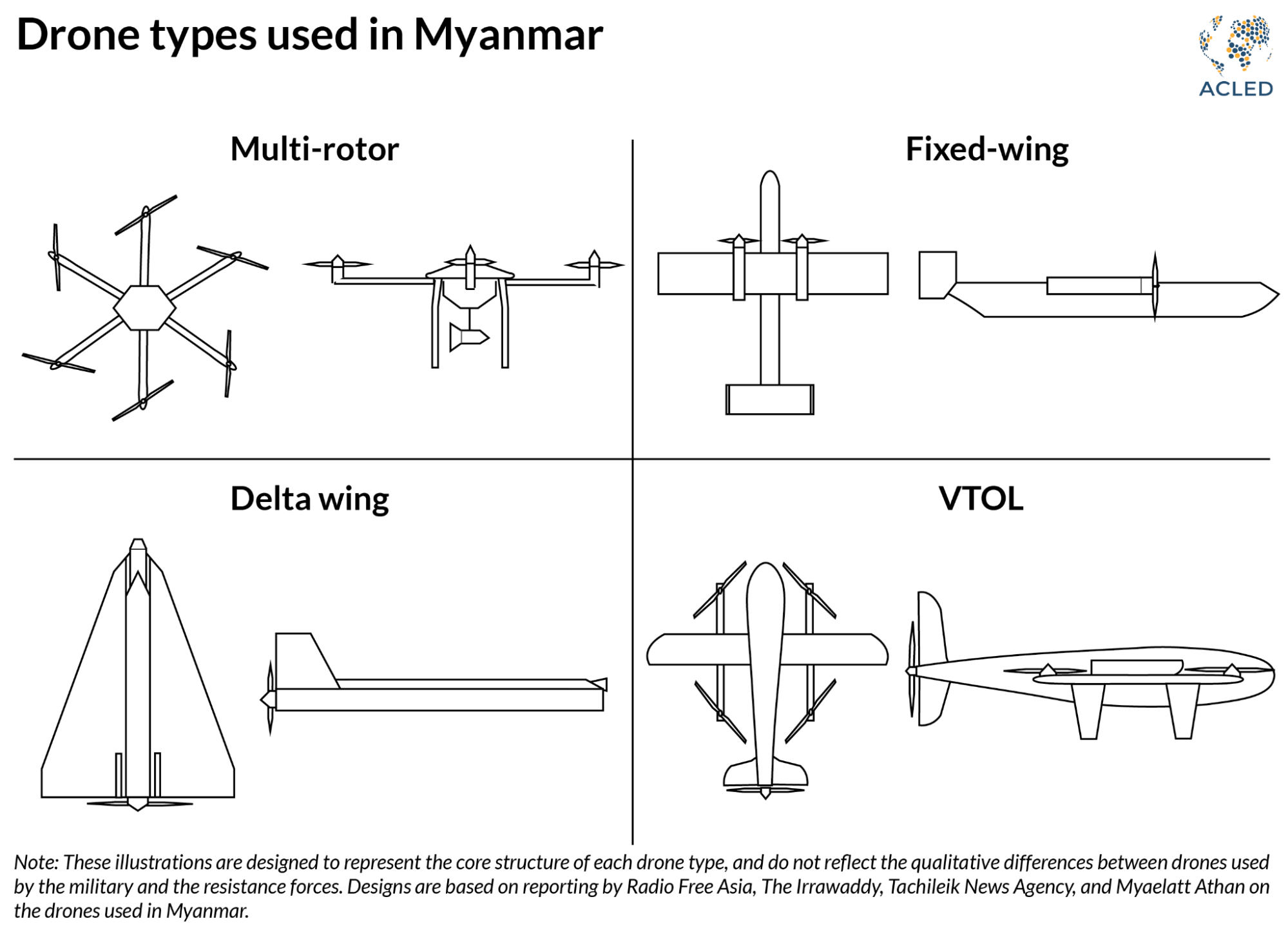

Two commonly used drones among resistance groups are multi-rotor drones, such as quadcopters and hexacopters, and fixed-wing drones. Multi-rotor drones can take off and land vertically, while fixed-wing drones launch horizontally and need a launching platform or manual assistance, though they offer longer flight ranges. The image below illustrates these two types of drones, as well as delta wing and vertical take-off and landing drones that are discussed in the next section. Resistance groups have modified drones in various ways, including by adding cameras and first-person view features, increasing payload capacities, and turning them into suicide or kamikaze drones designed to crash into a target and detonate.

These drones have been employed for various strategic purposes such as reconnaissance, disrupting military supply lines and reinforcements, engaging in combat, destroying high-value assets, and conducting high-profile attacks or assassinations. In a notable case, on 4 April 2024, resistance groups simultaneously attacked the Aye Lar military airbase and the military headquarters in Nay Pyi Taw, the military capital, with kamikaze drones. The groups claimed a successful strike on military targets, reporting that a fire broke out at the Aye Law airbase, where two military soldiers were killed and four others were injured. The military claimed it shot down seven of them.

In another high-profile attack, resistance groups launched five kamikaze drones during a visit by the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the military, Soe Win, to the Southeastern Military Regional Command in Mawlamyine on 8 April 2024. In a follow-up strike on 9 April, the groups claimed that drone bombs hit a stadium and a helicopter unit, destroying two military helicopters.

In late 2024, the increasing sophistication of drone technology enabled attacks on high-value military assets. On 11 November in Meiktila, resistance groups attacked the Shan Te airbase and 99th Light Infantry Division base with 24 drones, damaging two Y-12 aircraft and two weapon factories. This operation was a result of nearly one year of planning, and resistance groups lost a dozen drones during trials and the operation itself. Yet, resistance groups have also used drones for psychological warfare, even when lacking ammunition, by flying unarmed drones over bunkers and checkpoints to apply constant pressure on the military and lower troop morale.

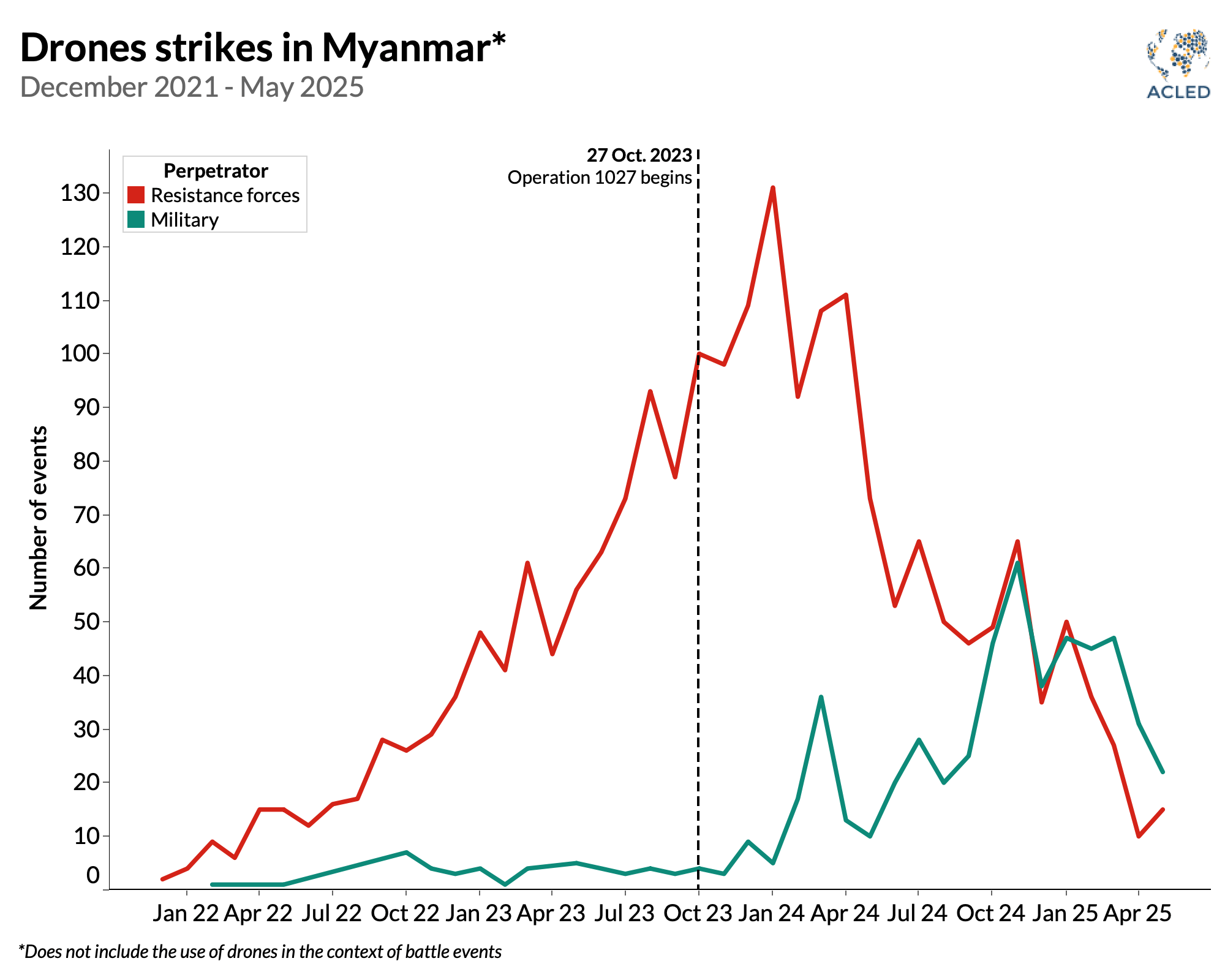

The resistance groups’ use of drones in combat has achieved battlefield success. One notable case was Operation 1027, a large-scale military campaign launched in late 2023 by the Three Brotherhood Alliance and its allies in northern Shan state. During the operation, resistance forces “swarmed” drones into battles, inflicting heavy military casualties and capturing large swaths of territory. According to a military soldier who retreated from one such battle, “bombs were dropping from the drones one batch after another like rain.” In another example, resistance fighters captured Shadaw town in Kayah state without engaging in any firefights or suffering casualties, thanks to drones.

Overall, drones have made up for the resistance groups’ lack of a major air force and heavy weaponry. Between 2022 and 2024, battlefield successes increasingly put them on an offensive footing against the military. But this served as a wake-up call for the military, which began prioritizing the development of its own drone program and enhancement of its air defense systems.

The military’s aerial campaigns

Given its capacity to maneuver high in the air from where it can attack unopposed, the Myanmar military maintains clear air superiority. This is its clearest advantage over resistance groups, many of which lack the heavy weapons needed to shoot down jets and other air targets. As a result, the military has increased its reliance on airstrikes since late 2023. Between January and May 2025, the military carried out 1,134 distinct airstrikes, compared to 197 and 640 during the same periods of 2023 and 2024, respectively.

Despite its air superiority, the military’s troop numbers have suffered from major attrition. Considerable territorial losses have led to the military failing to station troops in many parts of the country. Morale is low, soldiers often desert when confronted in combat, and many prisoners of war choose not to return to the military when captured and released. The military enforced its conscription law in February 2024, which legalized the conscription of young men aged 18-35 and women aged 18-27. However, the law is still failing to provide sufficient recruitment to replenish the military’s ever-weakening soldiery, leading it to forcibly recruit soldiers among those repatriated from foreign countries and vulnerable communities. This weakening of ground power, combined with a declining economy and a shortage of foreign currency to purchase jet fuel, has forced the military to focus on upgrading its in-house drone program.

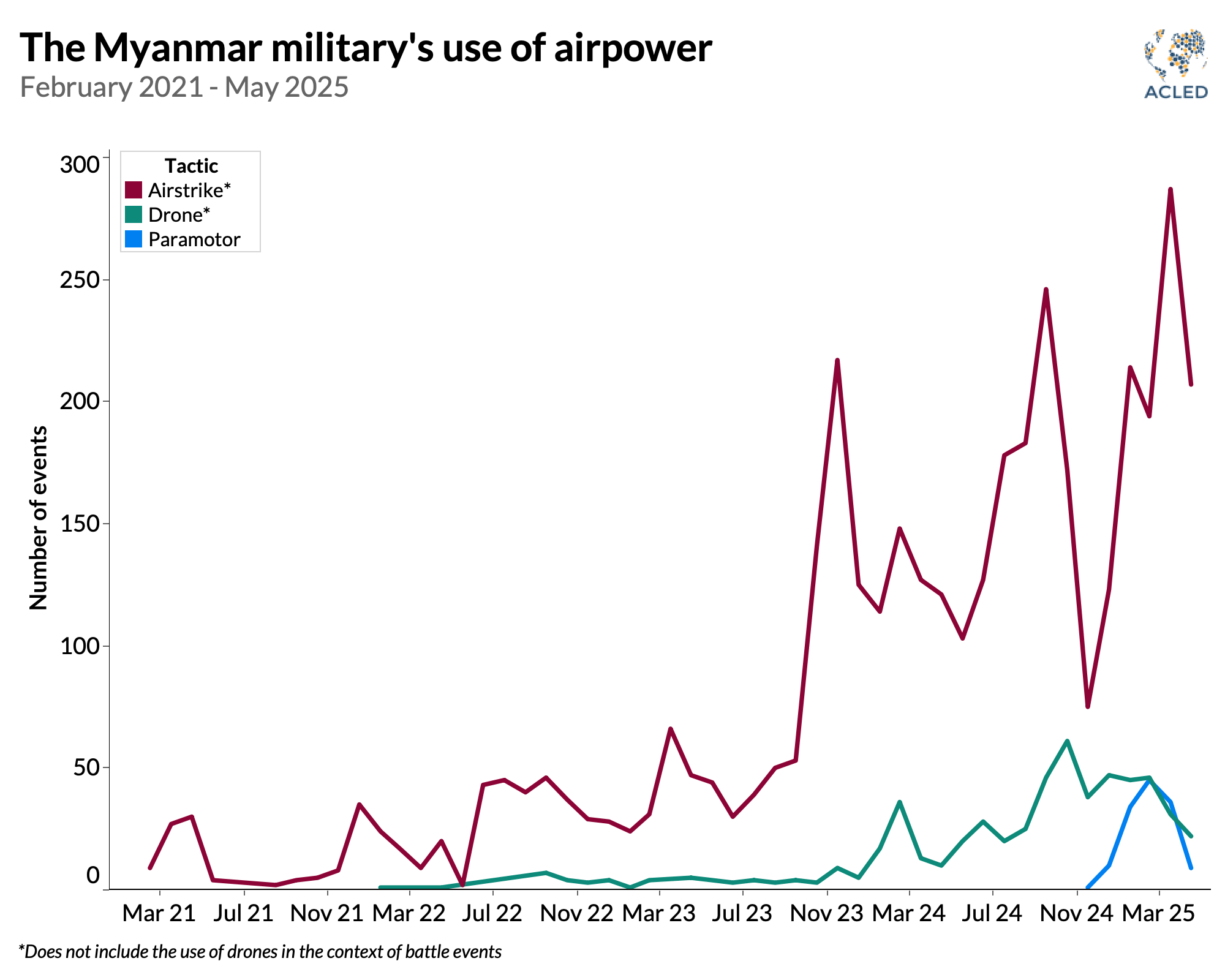

Since 2024, the military has complemented its aircraft and helicopter fleet with drones and paramotors (see graph below). These are less expensive and require less training to operate than helicopters and jets. Yet, drones and paramotors have demonstrated a higher degree of precision and lethality. The military’s first use of a paramotor — a power-motored paraglider seating up to three soldiers that has the ability to fire upon targets on the ground or drop bombs — was recorded in December 2024, when a paramotor injured two civilians in Taungtha township, Sagaing region. Since then, ACLED records over 120 military uses of paramotors and at least 70 related fatalities.

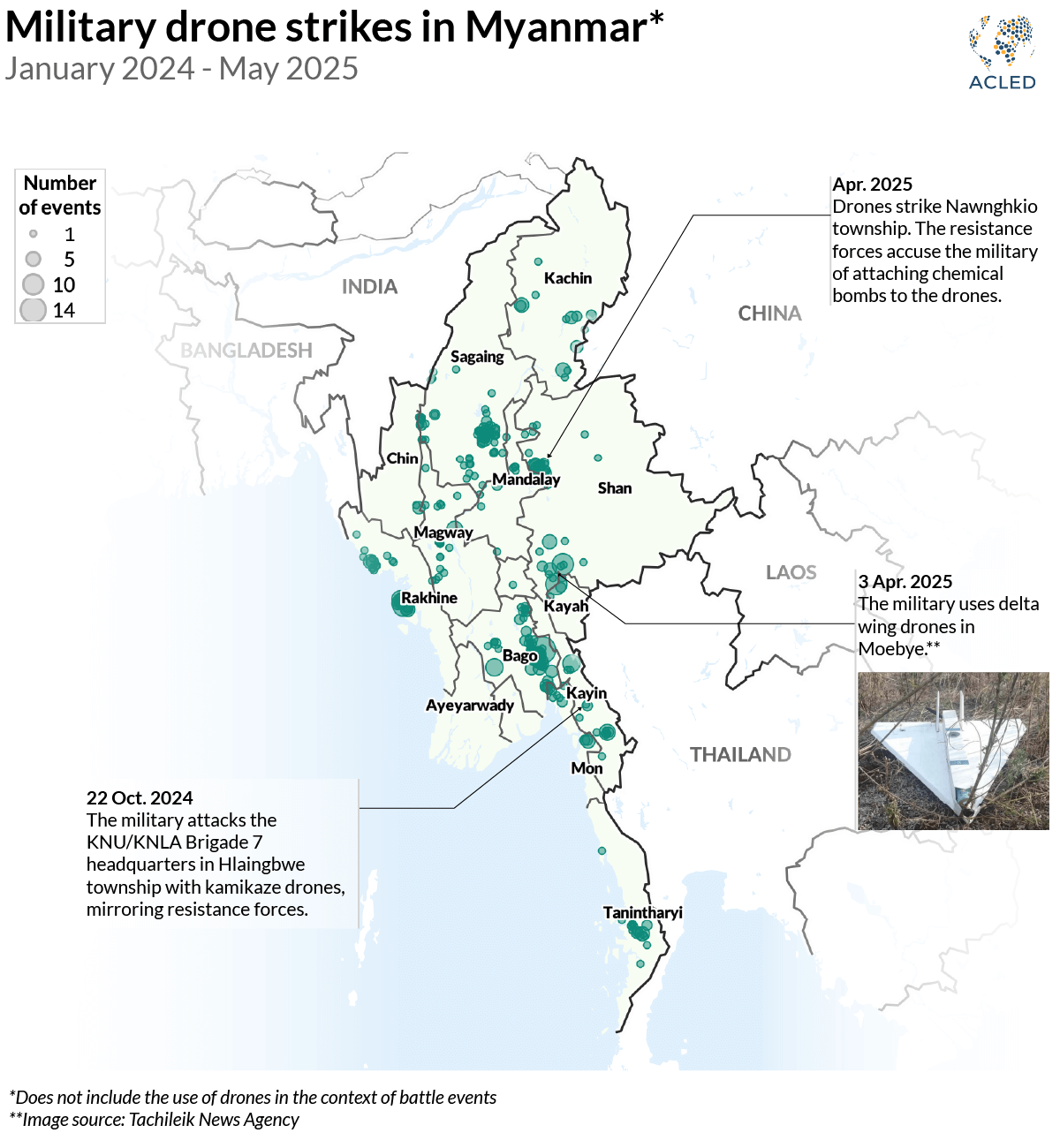

Paramotors are typically deployed in areas of mixed control or where resistance groups have minimal equipment, such as lacking access to the 7.62 cartridges and weapons required to shoot them down. The military has conducted more than 570 drone strikes against resistance groups and civilians in at least 340 locations. Military drone strikes have resulted in the deaths of at least 191 people, at least 158 of whom were civilians.

While the military’s drone operations did not significantly advance until 2024, it started using drones as early as 2014 and has been producing them locally since 2016.The first reported military drone strike in Myanmar took place in Myebon township of Rakhine state against the Arakan Army in 2020. The military also used drones extensively for surveillance during its initial killings of unarmed anti-coup protesters in 2021. For the military’s 77th Armed Forces Day on 27 March 2022, it flew hundreds of drones for public display. In November 2023, the military junta leader visited Chinese drone manufacturers and reportedly ordered thousands of drone parts. It also formed a dedicated drone unit following the acquisition of training support from China and Russia in early 2024. It now employs a variety of commercial and military-grade drones equipped with cameras, infrared sensors, and night vision for reconnaissance and combat (see the chart in the annex).

The military uses reconnaissance drones to guide artillery bombardment and identify the locations of resistance fighters, allowing air power to be called in for precision attacks. Kamikaze drones, however, will hover, identify targets, and then launch their own attacks. In many cases, targets do not have time to escape an attack once they notice a drone.As of May 2025, these drones were being used in at least three active conflict sites: Bhamo (Kachin), Nawnghkio (northern Shan), and Kawkayeik (Kayin).

In Bhamo, the military’s use of drones has dramatically slowed resistance advances. The Kachin Army (KIA/KIO) and its allies launched an attack on 4 December, initially taking several key sites such as the airport, but they are struggling to defeat the military in multiple other locations in the town. This is because the military deployed advanced drones with thermal imaging, forward-looking infrared technology, and night vision cameras that make advancing much more difficult.

Sophisticated drone attacks such as these enabled the military to recapture previously lost territories by inflicting heavy losses on the enemy. It recaptured Twin Nge village in Mogoke township of Mandalay region and Mae Poke and Naung Lin villages in Nawnghkio township of northern Shan state, which were under the control of Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), slowly working to push the PSLF/TNLA back from the gains it made during Operation 1027 and into Namsan and Mangton townships in northern Shan state.

A significant aspect of the military’s changing drone use is its mirroring of resistance groups’ strategies and localization processes. It implies the military is not only learning from its allies, such as Russia and China, but also from its adversaries. This is particularly true for the military’s drone battalions operating under the air defense and regional military commands in states and regions away from the military’s core bases. Here, the military employs modified commercial drones with either metal bombs, which are legacy munitions it manufactures the traditional way, or with plastic body bombs, which are improvised in much the same way as resistance groups. The military used an improvised drone in an attack on the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army Brigade 7 headquarters in Hlaingbwe township near the Thai-Myanmar bord

er on 22 October 2024 (see map below). The kamikaze drones it used share designs and specifications with those long made by resistance groups.

Further evidence of the military’s improvised drone use came during an attack in the battle in Moebye in southern Shan state on 3 April 2025 (see map above). During this attack, it used a drone made from styrofoam and a type of plastic called corflute that resistance groups named a delta wing drone for its similar wing configuration to an Iran-made Shahed-136 one-way attack drone. These examples have persuaded resistance groups that the military is copying their innovations. It is also possible that both sides are developing plans for drones from the same external sources, likely including China.

The military’s aerial campaign, now incorporating jets, helicopters, paramotors, and drones, has evolved throughout the war. The inclusion of drone capabilities compensates for the military’s human resource problems and helps reduce operational costs. In turn, more advanced drone technology has enabled deadly precision strikes, which can inflict heavy damage on the enemy, force them into a defensive position, and disrupt any semblance of peace in territories controlled by resistance groups.

The drone arms race

The military has been rapidly closing the gap in drone use, compared to resistance groups, since late 2024 (see graph below). The decline in drone use by resistance groups is attributed to the military’s increased use of advanced jamming devices and the disruption of their drone supply chains, among other factors.

The military requested that China block the export of dual-use items and drone parts to resistance groups during the junta deputy minister’s visit to the country in September 2024. It is also reported to have ordered the arrest of individuals selling and importing dual-use items domestically. As a result, resistance groups are increasingly unable to acquire all the necessary parts to modify their drones, and the cost of most drones has doubled since 2023. Agricultural drones used for combat, available for the kyat equivalent of US$3,000 in 2023, now cost around $6,250, according to an expert interviewed for this report. This price increase is the result of multiple factors, including China’s decision to close some of its land borders with Myanmar, which forced resistance groups to use alternative, more expensive routes to import drone components; the depreciation of the kyat; and inflation, as official sale channels were increasingly shut down.

Recognized as non-state actors, resistance groups cannot purchase arms and weapons or receive direct military assistance from other state actors. While some resistance groups claim to have the capacity to compete with the military in drone and electronic warfare, they have limited budgets and resources to counter the military’s upgraded drones.

Furthermore, commercial drones operated by resistance groups cannot bypass military jamming devices. Commonly referred to as jammers, these devices interfere with drone signals by severing the communication link between the drone and the person controlling it. This can cause the drone to crash, return to its home location, or hover in the air until the battery runs out. In battle scenarios where the military feels it cannot match the drone technology of its adversary, it uses jammers. In worst-case scenarios, drones have even hit civilians when they have fallen from the sky after losing connection. In one notable case on 22 November 2023, a drone with a bomb payload being flown by a resistance group in Muse was disrupted by a military jammer. It then crashed into the Zeyya Mingala Monastery, destroying it and injuring a novice monk.

The military now deploys upgraded jamming devices that can disrupt four-channel frequencies with a range as high as 1,000 meters in almost all of its major bases. Most resistance groups’ drones have only three channel frequencies. This has resulted in resistance groups losing drones, being more cautious with them, and using them only under secure conditions, which has impacted their overall drone usage. While resistance groups equipped with better resources and technology, such as KIO/KIA, can overcome such barriers, smaller resistance groups are forced to switch tactics when confronted by jammers. One small resistance group operating in the Sagaing region claims to have pivoted back to on-the-ground fighting after losing seven drones to military jammers. The resistance groups’ lack of counter-measures and limited budgets are leaving them behind in the drone arms race, in the military’s favor.

While the military is yet to reverse many of the gains made against it since the 2021 coup, its recent improvement in drone use is effectively undermining the resistance’s previously strong drone capabilities. This is particularly true for tactical drone strikes that occur in isolation outside of pitched battles. During the battle for Falam town in Chin state between 2024 and 2025, when its remaining troops were besieged in the town’s last standing military base, the military carried out non-stop jet airstrikes and left drone jammers on. This led the attacking resistance fighters to capture the base conventionally, through pressure from small arms fire and ground positioning. If resistance groups push the military into using jammers more often, achieve better coordination between each other, or combine the use of different weapons, they may be able to sustain their gains and counter the military’s increasingly effective use of drones, at least on the battlefield.

Are drones changing warfare in Myanmar?

The accessibility, ease of modification, and cost-effectiveness of drones enable both resistance groups and the military to achieve military objectives while minimizing combat casualties. While it remains to be seen whether drones will ultimately be a game-changer in Myanmar’s conflict, both sides increasingly integrate drones into their military strategies, and 2025 appears to be the year that the military may gain a clear advantage. However, resistance groups will continue trying to improve their drone modification and weapons production processes, flexibly adapt their deployment of drones, and prioritize dismantling the military’s armaments production facilities, where primers, guns, bombs, and drones are mass-produced, to rebalance the scales.

With technical and military support from allies such as China and Russia, the military will only increase its use of drones in its counter-offensive operations. In the absence of improved counter-measures by resistance groups, it will continue to dominate Myanmar’s airspace with larger aircraft like fighter jets, helicopters, paramotors, and its newest addition of gyrocopters. But given that the military is stretched so thin across multiple battlefronts, this air superiority is unlikely to decisively shift the overall balance of power on the ground in its favor.

However, air superiority does enable the military to continue targeting civilian-populated areas; destroying civilian infrastructure, such as health care clinics, markets, and schools; and disrupting civilian livelihoods. This hinders resistance groups’ efforts to build lasting and robust administrations in the areas they control and provide public services to civilians.